By Josh Foerschler, P.E., M.SAME

Standing up new sensitive compartmented information facilities requires a thorough understanding of design standards and best practices for these secure structures, along with the unique requirements for each specific location.

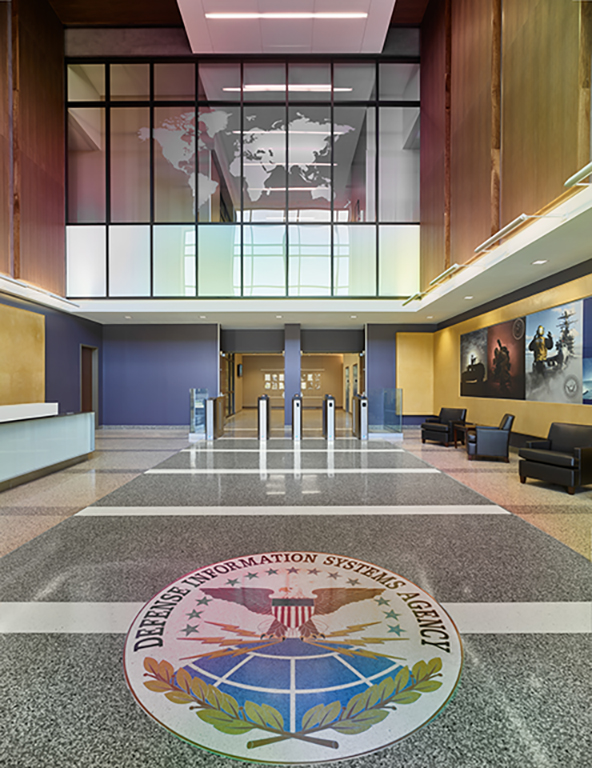

PHOTO COURTESY BURNS & MCDONNELL

Enabling classified or otherwise secured work requires carefully designed facilities to protect those vital interests. In the United States alone, millions of documents are classified every year. If someone needs to access this information, they generally do so in a sensitive compartmented information facility (SCIF).

SCIFs are extremely secure areas, ofen within other facilities, where sensitive information can be stored and viewed by authorized government officials and defense contractors. Thousands of SCIFs already exist. They can be found in government buildings, military installations, embassies, and contractor offices. And with surveillance techniques becoming ever more sophisticated, these secured spaces are essential for both storage and controlled access of the burgeoning number of highly classified documents. Designing and constructing these secured spaces, therefore, requires careful consideration and the utmost attention.

Similar to a construction trailer at a job site, these trailers are developed with SCIF building standards in mind. As long the intended site has a pad and power supply, the modular unit can deploy in a plug-and-play style.

Designing Secure

The physical design of a SCIF and the ways in which it can be built are carefully defined by federal directives. In essence, SCIFs are designed to block both sound and electronic signals from leaving the secured space.

Walls, foors, and ceilings must be constructed with a specific thickness for both drywall and concrete. The secure perimeter is sometimes designed with prescriptive-based design. More commonly, it follows a performance-based set of criteria. Windows are not typically allowed since they could permit the space to be compromised visually. Doors are equipped with special combination locks, complying with Federal Standard FF-L-2890C requirements. Entrance security can be supplemented by card readers and potentially guard personnel. Power and ventilation systems are also highly regulated to prevent physical access or acoustic weaknesses.

Cellphones and similar mobile devices are not permitted within the SCIF in order to prevent any recording of sensitive data. Motion sensors are commonly used as well to detect any activity when the facility is not in use.

A SCIF can be a single room or many rooms and can utilize a large area, such as the 41,000-ft² of designated secure space within an overall 165,000-ft² headquarters facility for the Defense Information Systems Agency built a few years ago at Scott AFB, Ill. SCIFs can consist of office spaces and cubicles, conference rooms, or a series of other configurations.

Types of Projects

To meet the increasing need for extremely secure facilities, there are a variety of options available to meet SCIF standards. These spaces can be built new, when a facility is being designed and constructed, or they can be implemented as retrofits of existing spaces. The secured area might be a permanent space, such as the situation room at the White House, or it could be temporary for purposes of a shorter-term mission or program.

Retrofitting. Retrofitting existing spaces into a SCIF can be a complex endeavor. Essentially, it requires erecting a room within a room. The existing space often needs to be stripped down to bare walls, ceiling, and studs for reconfiguration. Additional layers of drywall and insulation may be needed to achieve the necessary sound transmission class rating, effectively shrinking the available space. If stud sizes are insufficient or too widely spaced, existing walls either need to be rebuilt or new stud partitions with the proper gauge and spacing must be built.

Plumbing piping (such as for domestic water and sanitary sewer) typically is not allowed within the SCIF boundary. Sprinkler systems are usually zoned for only the SCIF area and do not pass through from one unsecure area to another. Electrical systems, information technology, and ventilation access also likely would need to be replaced in a retrofit.

Some of the benefits of pursuing a retrofit include the presence of a building with existing utilities, which eliminates the costs of establishing fresh connections. Additionally, and particularly for prime contractors, retrofits can make it more feasible to have several SCIF suites within the same facility. Each might serve a different program, and access to each is limited to allow only the necessary personnel with the appropriate clearance into each secured area.

Modular units. Modular SCIF units represent another option. Similar to a construction trailer at a job site, these trailers are developed with SCIF building standards in mind. As long as the intended site has a pad and power supply, the modular unit can deploy in a plug-and-play style.

The primary advantage to this, especially as a short-term solution, is speed to market. Deploying a ready-built module is faster than building new or retrofitting, as long as the module is set up to accommodate the necessary needs.

Verification Steps

Federal guidelines require construction of SCIFs to be performed by U.S. forms and citizens. But standing up a SCIF requires more than mere knowledge of the applicable design standards. Given the intricacies of a specific customized space, unique items that might be challenging to procure, and all the necessary approvals once construction is finished, the amount of time and money needed to complete those projects can vary significantly. While there is not a formal list of approved vendors to stand up SCIFs, working with companies with proven experience designing and building these highly secure spaces can help expedite the process.

Typically, the government assigns an accrediting officer to the project. Normally the owner’s site security manager inspects and approves items as the SCIF project progresses, reporting back to the accrediting officer. The objective is to see that the facility meets code and that everything is installed according to the program’s design requirements.

After construction, personnel responsible for the execution and validation of the secure program will make a final determination of whether the space was built to the correct specifications and has all the appropriate documentation before granting final approval for work to begin inside the space.

Strong Standing

The principle of “security in depth” is a time-tested approach that uses multiple layers of security to provide redundancy and enhance the protection of valuable assets. The more layers that a malign actor needs to penetrate, the longer it takes, increasing the odds of them being caught before important information is compromised.

That same principle forms the basis for the concept of a SCIF. Soundproofing, sightproofing, controlled access, and other measures are applied to keep sensitive information restricted to only those with appropriate security clearances. By the same token, having adequate SCIFs available to store the necessary material and enable access for approved personnel is essential in helping contractors and government officials take full advantage of those materials.

While SCIFs are not a foolproof solution, they play a vital role in national security and in the development of advanced technologies. Setting up a SCIF does not require an entirely new building, and, depending on the precise need, it might not even require a permanent facility. But successfully deploying a new SCIF depends on precise design and implementation, informed by thorough understanding of the complex requirements involved.

Partnering with firms that have a proven track record of designing and building SCIFs can expedite the results, improve outcomes, and save time and money over the long term.

Josh Foerschler, P.E., M.SAME, is Senior Project Development Manager for Aerospace & Defense, Burns & McDonnell; jfoerschler@burnsmcd.com.

More News from TME

-

Developing an Engineering Standard of Care for Cyber Safety

There is growing urgency to secure the nation’s critical infrastructure from a cyberattack, which will require improvements in both federal policies and day-to-day operations to strengthen response and recovery from incidents. -

Improving Escalation Forecasting in Federal Construction

A newly developed escalation forecasting methodology for major capital acquisition projects improves on previous models with a Monte Carlo simulation to increase accuracy. -

Reducing Health Risks When Working in Confined Spaces

Completing an audit of the hazards, permits, and roles and responsibilities associated with confined spaces can help alleviate health risks and enhance worker protections around these aspects of facilities.