Big Job, Small Solutions:

Completing a Complex Remediation in Remote Alaska

By Karina Quintans, M.SAME, Monte Garroutte, and Monica Oakley, PMP, M.SAME

At a remote federal remediation site in south-central Alaska, inaccessible by road, barge, or large planes, leveraging the local community and a fleet of snowmobiles and small watercraft allowed for 1,100 bags of contaminated soil to be transported for offsite disposal.

After 363 trips by snowmobile and 163 trips by small watercraft, the last of 1,100 bags of contaminated soil was transported out of Skwentna, Alaska, for offsite disposal by mid-summer 2024, culminating a rare five-year contract in support of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The effort to complete this uniquely extensive project underscores the value of collaboration, of community engagement, and of creative (even if uncomplicated) solutions to large-scale challenges.

Built in 1943 by the Civil Aviation Administration to provide temporary airway navigation and communication support to the Department of Defense, the FAA station in Skwentna once stood near the confluence of the Skwentna and Yentna Rivers. Decades later, a substantial environmental remediation project at the site was required to clean up and dispose of contaminated soil. The remote location would pose myriad challenges and require a multi-pronged, logistically complex remediation approach.

Though just 65-mi northwest of Anchorage, but with a population of only 50 people, there are no roads going into or out of Skwentna. The town is accessed by bush planes, small watercraft, and snowmobile. The area is a popular destination for hunters and fisherman, is a regular destination for recreational snowmobilers from Anchorage, and is the first check-in point in Alaska’s historical Iditarod.

The key to the project’s viability proved to be partnering with the community, which used small equipment to remove large quantities of contaminated soil.

Leveraging Community

Despite frequent visitor populations, Skwentna lacks the infrastructure needed to efficiently and cost-effectively execute a substantial environmental remediation project that required the mobilization of 40,000-lb of chemical amendment and the transport and disposal of approximately 600,000-lb of contaminated soil. The airport runway is simply not large enough to land a C-130 cargo plane, and the local rivers are too shallow, too narrow, and too braided for a large barge to do the same.

Under the five-year contract with the FAA, Brice Environmental, as an Alaska Native Corporation, knew that partnering with the local community was essential. This approach not only met the unique project objectives, it supported the local economy by leveraging nearby capabilities. Given Skwentna’s recreational popularity, residents had long set up hauling services for hunters, fishermen, and their private cabins, using snowmobiles and small watercraft. With their knowledge of the winter conditions and summer landscape, nearby access routes, as well as how and when to most efficiently and safely transport parts, supplies, and other needs by snowmobile and small watercraft, the Skwentna community was best suited to perform the haul-in of the chemical amendment and other supplies, and the haul-out of contaminated materials.

The reliance on small equipment for transport and disposal drove the contract period of performance of five years. The last three years of the contract were specifically needed to complete the haul-out of contaminated materials. Instead of one or two barge or cargo plane trips in a single season, Skwentna required dozens of smaller trips by locals with small machines. This constraint focused project planning on the reduction of contaminated material requiring offsite transport and disposal.

Engineers designed a two-part solution: first, a two-acre landspread to treat contaminated soil with high concentration of petroleum-oil-lubricants through biodegradation and backfilling the excavation areas; and second, in situ chemical oxidation of contaminated soil with low concentrations, as well as any contaminated groundwater at the water table level to meet cleanup regulations.

Challenges Afield

Once the project was ready for mobilization, additional, and highly unforeseen, challenges emerged. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic delayed field execution for 18 months. Only limited mobilization of supplies and site preparation were performed to keep the project on schedule.

Full mobilization occurred finally in fall 2021 when a two-person field team spent 10 days clearing the heavy second growth of forested worksites to facilitate the excavation of 1,500-yds³ of soil and debris contaminated with petroleum-oil-lubricants, pesticides, metals, and polychlorinated biphenyls for offsite disposal. An additional 800-yds³ were removed for treatment at the landspread. The team also performed the removal of an unpermitted dump being eroded by the Skwentna River that threatened a release of contaminants into anadromous riparian waters, as well as riverbank restoration.

Instead of one or two barge or cargo plane trips in a single season, Skwentna required dozens of smaller trips by locals with small machines. This constraint focused project planning on the reduction of contaminated material requiring offsite transport and disposal.

Field Execution Phase. Despite resolving the mobilization constraints, the project team still encountered challenges during field execution. At the unpermitted dump, the river slough was eroding the riverbank, carrying polychlorinated biphenyls-contaminated debris downstream. Excavations were performed when the slough was empty of water. A temporary hydraulic control diversion upstream and downstream of the slough was constructed with liners and supersacks filled with clean soil to protect against the possibility of rising water during excavation. Permitting was extensive and involved multiple agencies and organizations each field season.

By fall 2022, fieldwork was largely completed. Stockpiled onsite were 1,100 1-T bags of contaminated soil ready for transport and disposal. The size of the bags was intentional, and important for two reasons. First, because of the inability to mobilize a crane to the project site, bags had to be small enough for a skid steer to lift onto and off of the watercraft. Second, multiple smaller bags ensured proper weight distribution when loaded onto the watercraft, ensuring safe transport and disposal via the Skwentna River.

Haul-Out Operations. Once the weather and trail conditions were right for snowmobiles, the locals began the haul-out, often transporting one to two bags at a time, using the frozen river as the road. They traveled about 65-mi to Deshka Landing in Willow, which was located close to a major highway. Hauling operations halted when the access routes were no longer safe for snowmobile travel. As summer arrived and the river ice had receded and early-season high water levels were flowing, locals replaced snowmobiles with small watercraft that traveled three hours downriver to Deshka Landing, carrying six bags at a time. A total of 40 bags, each weighing 1-T, were staged at Deshka Landing, enough to fill two containers. Operators transferred the bags onto trucks for transport to Anchorage, where they were loaded onto a barge to Seattle, then transported to a permitted landfill in Oregon by way of railroad.

Skwentna locals often worked 12 hours a day, even in the dark winter months, using headlamps to illuminate the trail. As the town is the first checkpoint for the Iditarod, bag transport was paused for around 14 days in March to allow for trail breaking in preparation for the race and for the race to run its course through Skwentna.

Planning Pays Off

Completing the remediation at the former FAA station in Skwentna was a complex endeavor with multiple contaminant categories, each with different fate and transport considerations. Personnel encountered site access difficulties; high ecological risk and stringent cleanup criteria; in-situ and ex-situ treatment and disposal methods; work within an anadromous river; landfill waste segregation; multi-season work; extensive permitting requirements; and a unique small watercraft and snowmobile waste transport strategy. The coronavirus and short Alaska field season only complicated matters.

While none of the solutions was unfamiliar nor overly innovative, the enormity of the job required meticulous planning to execute work in short windows using small equipment and over an extended timeline. In the end, the project went off without a hitch.

Karina Quintans, M.SAME, is Owner/Writer, JebelWorks LLC; kquintans@comcast.net.

Monte Garroutte is Environmental Project Manager, and Monica Oakley, PMP, M.SAME, is Senior Program Manager, Brice Environmental Services.

Published in the January-February 2025 issue of The Military Engineer

Check Out Related Articles From TME

-

Deploying Renewable Generation Through Small-Scale Hydropower

A field demonstration and ongoing investigation of modular hydrokinetic turbines by the U.S. Army Engineer Research & Development Center’s Construction Engineering Research Laboratory illustrates the potential applicability for using the technology on military deployments. -

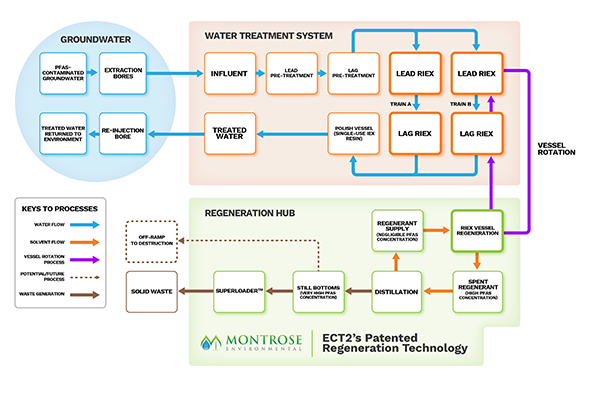

Rethinking Traditional Treatment Systems for PFAS Remediation

At two U.S. Air Force bases impacted by historical releases of aqueous film-forming foam, innovative methods in treating PFAS in both surface water and groundwater provide examples of success in safeguarding health for military personnel and nearby communities. -

Tackling Restoration Projects With Amphibious Excavators

When faced with soft and wet underfoot conditions, such as at a recent channel dewatering, excavation, and repair project for USACE Galveston District, amphibious excavators offer a scalable way to contour difficult site characteristics. -

Big Job, Small Solutions: Completing a Complex Remediation in Remote Alaska

At a remote federal remediation site in south-central Alaska, inaccessible by road, barge, or large planes, leveraging the local community and a fleet of snowmobiles and small watercraft allowed for 1,100 bags of contaminated soil to be transported for offsite disposal. -

Regenesis Offers Full-Spectrum PFAS Remediation

For project stakeholders and remediation managers confronted with PFAS, Regenesis demonstrates why in situ treatment using Regenesis’ PlumeStop® colloidal activated carbon (CAC) is a game changer. -

100 Percent PFAS Compliance with Regenerable Ion Exchange Resin

The operational success of a RIEX system spotlights its successful approach to combating PFAS in an effective and economical manner. (Sponsored Content)